In Biochemical Engineering, the goal is to make everything sustainable

Microorganisms like yeast could produce any aromas, flavours or natural substances that we desire in a more sustainable way. Professor Sotirios Kampranis and his research group are trying to solve how to make enough for the future.

Hoppy beer, floral perfume and minty toothpaste. Did you ever wonder where these smells and flavours come from? The molecules carrying aromas are extracted from plants like lavender and mint, but overharvesting of these crops for their natural aromas is bad for the environment and for biodiversity.

Industry often turns to organic chemistry to make enough of these aromas to meet global demand. Many of these chemicals are derived from petroleum, just like other bioproducts like rubber, plastic and dyes. That is neither good for the planet nor us.

The Biochemical Engineering research group is set to solve this problem. The group’s goal is to replace harmful chemical synthesis and overharvesting of natural resources with biological synthesis.

“None of the methods we use right now for many biomaterials is sustainable or environmentally friendly,” said research group leader Sotirios Kampranis, who is a professor in the Department of Plant and Environmental Science at University of Copenhagen.

“We need a radical change in the way that we make all these materials in order to build and maintain a green planet. And we need to develop the technology to do it.”

So is there a way to make this stuff without overharvesting or relying on fossil fuels? The answer is yeast.

Welcome to the yeast lab

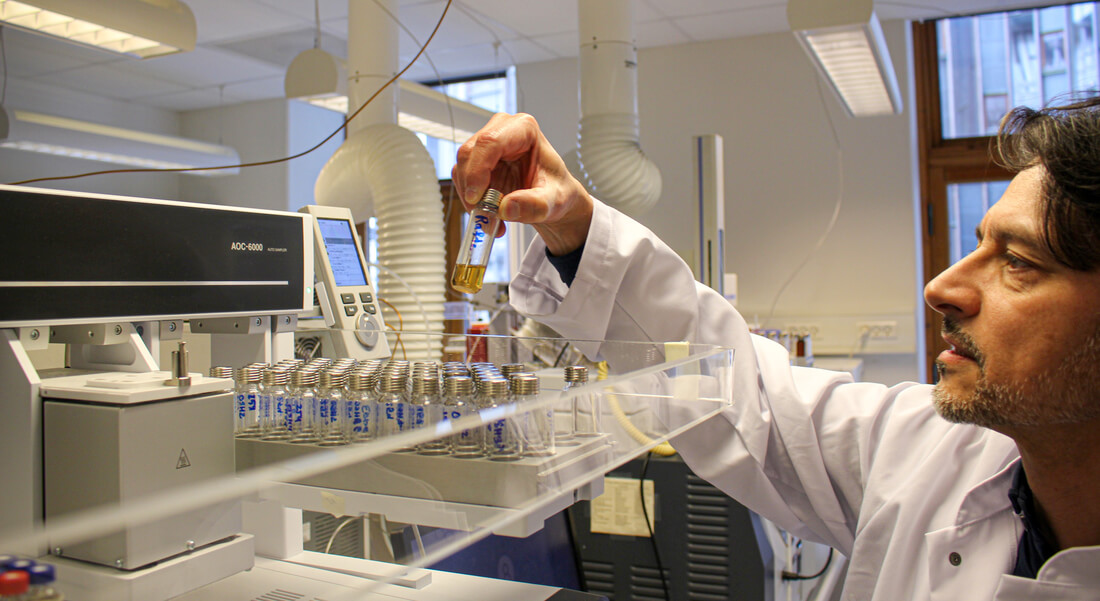

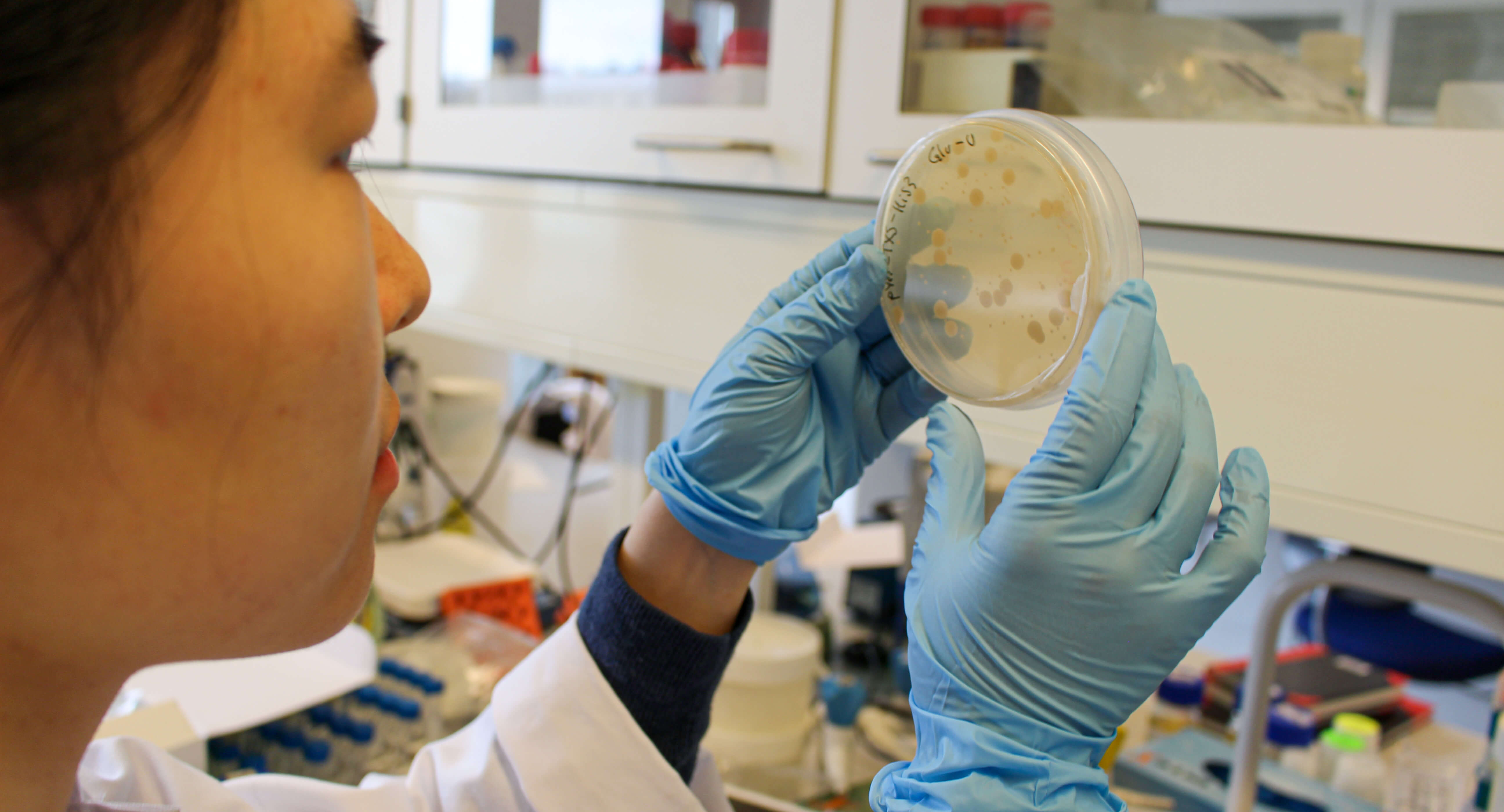

Placed upon shaky platforms, conical flasks swirl around milky solutions next to bubbly fermenter silos. Kampranis and his team are engineering yeast to produce bioproducts, and this is where the magic happens.

“In our lab, we teach microorganisms how to make the different products. We feed them sugar, we grow them inside a big fermenter, and they produce aromas, fragrances and dyes. They produce polymers like rubber. They produce natural pesticides by mimicking the same compounds that the plants use to protect themselves. No toxic materials. No destruction of the environment,” Kampranis said.

He has already used this method to create the compounds that make a non-alcoholic beer taste just like regular beer. His team turned baker’s yeast cells into microfactories that can be grown in fermenters and release the aroma of hops.

Hops is a thirsty crop. You need 2.7 tons of water to grow one kilogram of hops. With the yeast method, you only need half a glass of water and some sugar, but not the plants.

“Instead of overproducing and overconsuming, we minimise the cycle and add just as much sugar as we need to make exactly the molecules we need. Now we can use the farmland that was used for hops to produce food instead.”

In this lab, yeast seems to offer nearly endless possibilities.

“The sky is the limit,” says Irini Pateraki, an assistant professor working the lab.

“It’s only our minds that are restrictive. Nothing else really. We are closer to having more applications every day. It would be stupid, in my opinion, not to use this technology to make life on the planet better.”

Rubber from lettuce?

“This is where we try to make rubber,” Kampranis says.

Not all natural polymers (substances made from smaller molecules forming into larger molecules) are for consumption and personal care. Natural rubber is an isoprene compound sapped from the rubber tree.

Around 90 percent is produced in Asia, with Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia accounting for 72 percent of the world’s natural rubber supply. But with the rapid motorisation of Asia, natural rubber is becoming a precious commodity, so products like car tyres also contain synthetic rubber, which is another petrochemical.

Rubber trees are not the only latex-producing crop. In fact, your typical gem lettuce from the supermarket oozes white latex when you chop it, making it a great model plant. Getting yeast or the dedicated cells in lettuce heads, called laticifers, to produce polyisoprene strong enough to replace natural or synthetic rubber may seem like a long journey. Nevertheless, that is where the Kampranis lab is headed.

“We promote biodiversity instead of growing monocultures of rubber trees. We could actually have forests where the rubber trees currently grow.”

SDGs provide a frame for sustainability

For a research group with a drive for green innovation, the sustainable development goals (SDGs) offer a common language and framework to address these issues.

“All the projects we have in our lab right now try to address at least one of the SDGs. In my lab, we are 100 percent motivated by sustainability. This is what we do. For us, the long-term goal is to make everything sustainable,” Kampranis said.

He finds that the SDGs help researchers in their daily life to convey their thoughts and approaches in a way that makes it easier for other people to understand them.

“Everyone involved, from technology readiness level 1 to 10, need to be on the same page. The SDGs give us a common framework in which everything fits.”

For the young scientists joining the lab, working with sustainability is a highly motivating factor.

“I really feel like I’m contributing to society with this project,” said Anzhou Xin, a postdoc working on the project to make the yeast produce rubber.

“Once we succeed, we can change the natural resources that the rubber plantations occupy for agricultural space and replace the need for petroleum-based synthetic rubber. In the long run, we are going to be relying on a renewable source.”

Kontakt

Andreas Berg Jakobsen

Communications officer

Email: abja@plen.ku.dk

Phone: +45 35 33 31 76