Researchers discover how to turn bitter lupins sweet

Lupin seeds are high in protein and could become a sustainable alternative to imported soybeans, but many varieties contain alkaloids that make them toxic and bitter. Now researchers from University of Copenhagen have identified a gene that is responsible for creating these bitter compounds. Their discovery could lead to an increased cultivation of lupins for plant-based foods.

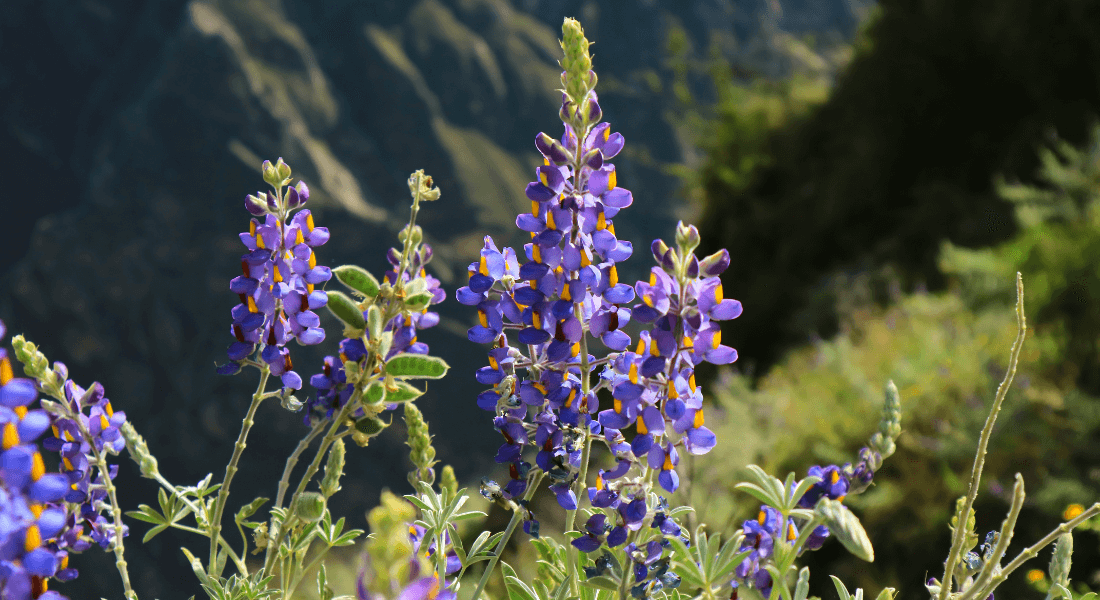

Archaeologists have found them in the tombs of pharaohs in Egypt. You can get them as bar snacks in Italy and Portugal. Yet chances are that you know lupins for their colourful flowers more than for their golden protein-packed seeds.

Lupin beans normally contain alkaloids, which make them bitter and toxic. Before you can eat bitter lupins, you first have to soak them in water several times for about a week, until the bitter alkaloids are gone. In the 1930s, breeders in Germany selected low-alkaloid varieties of white lupin (Lupinus albus) and narrow-leaved lupin (Lupinus angustifolius) - but no one knew what made some lupines bitter and others not.

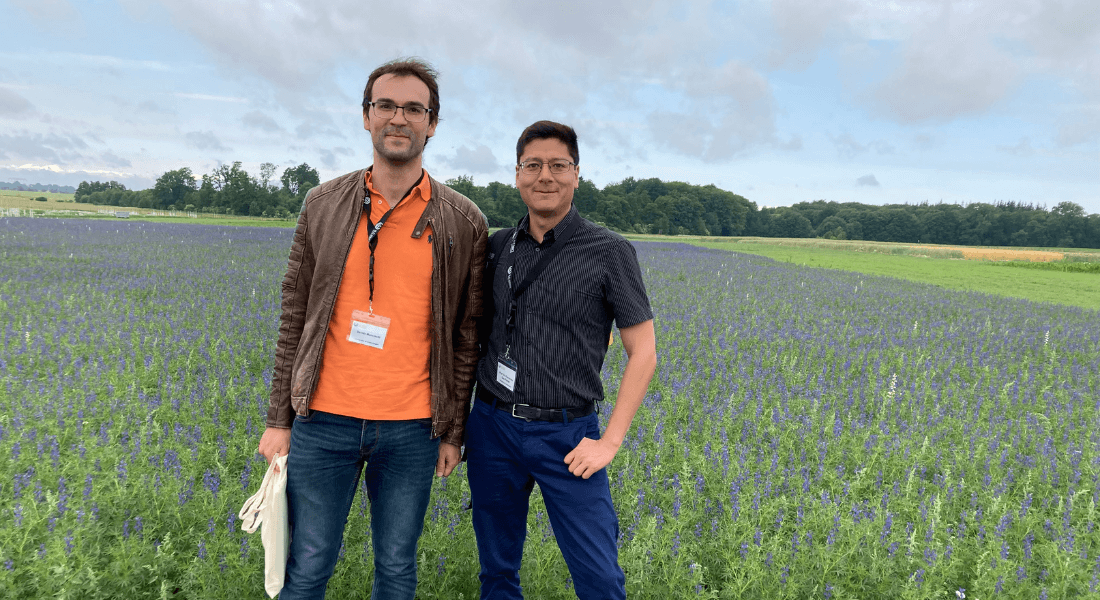

Davide Mancinotti and Fernando Geu-Flores of the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences at the University of Copenhagen have identified a gene that is responsible for making alkaloids in lupins, paving the way for lupins as a protein crop to replace imported soybeans. Along with an international team of researchers, they had their study published in Science Advances.

“We set out to discover the gene that enabled sweetness in white lupin. We knew that the sweet trait must be a result of some mutation, but the mutation as well as the gene in which it arose remained unknown. Now we know both,” Fernando Geu-Flores said.

The role of acetyltransferases was a surprise

How lupins produce alkaloids is a mystery. Alkaloids have a complex chemical structure, but they derive from a simple amino acid called lysine.

“The pathway is a sequence of transformations that convert one simple molecule into a very complex one. In each step, there is an enzyme encoded by a gene in the plant’s DNA that carries out the transformation. We knew the first two steps, but there were at least four more. Then we stumbled upon an acetyltransferase,” said Davide Mancinotti.

The importance of this enzyme wasn’t apparent at first, as acyltransferases were not predicted to take part in the pathway.

“Acetyltransferases put a tiny acetyl group on the molecule, but there is no trace of this in the final alkaloids. What we believe now is that the first two genes start the pathway, then the acetyltransferase adds an acetyl group and this helps the subsequent transformations. And somewhere before the end of the pathway, the acetyl group is removed,” said Fernando Geu-Flores.

They tested their theory in narrow-leaved lupin, of which there are both bitter and sweet varieties. By screening hundreds of thousands of bitter seeds, they were able to find one in which the acetyltransferase gene was mutated. The resulting plants had much lower alkaloid contents.

Andean lupin contains up to 50 percent protein

The discovery means that you could take bitter lupins, even species growing in the wild, and turn them into sweet versions that farmers can cultivate and grow more reliably, for instance as meat replacements in plant-based foods.

Lupins can tolerate cold and dry climates better than soybeans. That is just one reason why we could all be eating lupins in the future.

“Lupins are super high in protein. For instance, the wild Andean lupin (Lupinus mutabilis) can reach an impressive 40-50%. I don’t know of any other legume with such a high protein content. Most lupins contain between 30-40% protein, which is similar to soybeans. Like other legumes, lupins fix their own nitrogen from the air. Also, they do not contain any starch, which fava beans and soybeans do,” Fernando Geu-Flores said, as we share a bowl of salty brined lupini beans from a jar.

“And they taste pretty good."

Contact

Fernando Geu-Flores

Associate Professor

Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences

University of Copenhagen

Phone: + 45 35 33 28 52

Email: feg@plen.ku.dk

Davide Mancinotti

Postdoc

Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences

University of Copenhagen

Phone: +45 35 32 60 95

Email: dm@plen.ku.dk

Andreas Berg Jakobsen

Communications Officer

Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences

University of Copenhagen

Phone: +45 35 33 31 76

Email: abja@plen.ku.dk